by Sheila Hyland, Operations Manager, Luminari

“Are you sure you want to go through with this?” asked my dad on my wedding day. “Yes, dad. I’ve made up my mind—throw them out!” And with that, my dad did throw out every single letter written to me over six years by my long-distance ex-boyfriend, Bill, whom I thought I’d be walking down the aisle with but who instead ended up breaking my heart. I married someone else that day but, oh, how I regret tossing those cherished missives!

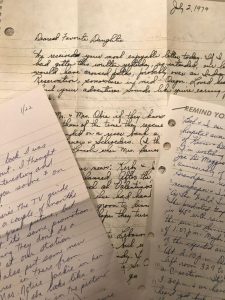

I still have, packed away in dusty, yellowing boxes in the attic, just about every other letter ever written to me through my college years. Back when the price of a long-distance phone call was prohibitive, before Skype, and before tweets limited our musings to 140 characters, our way of communicating with anyone who lived farther than driving distance was by hand-written letter.

I still can remember skipping to the mailbox, breathless over the idea that someone special (back to that ex-boyfriend again) might have written to me–a sign as my grandma used to say that “somebody loves you today!” I could tell when a letter had arrived from Bill because I knew his handwriting in an instant and sometimes he’d mist the envelope with the musky scent of his cologne. I could almost feel his presence in those letters, always written on college-ruled notebook paper. I wrote to him just as often. Our pages to each other were filled with professions of love, news of the day, observations about life, and doodles that have today been replaced by homogenized emojis.

Mom and dad wrote to me often when I was away from home. One of those letters arrived the summer after I turned 16. I was “roughing it” at a ranch in Eastern Oregon, building fences and digging holes–by choice, I might add. My mother wrote that my three brothers were definitely not missing me; my father wanted to know how I was surviving for two weeks without makeup.

During the Civil War and World Wars I and II, letter writing was the main form of communication. As there were no cell-phone cameras to capture the reality of war to send back home, soldiers relied on the eloquence of their words to paint a picture for their loved ones. Private Albert Ford used a scrap of paper to write to his wife, Edith, in 1917 during World War I. “So dear heart I will bid you farewell hoping to meet you in the time to come if there is a hereafter. Know that my last thoughts were of you in the dugout, or on the fire step my thoughts went out to you, the only one I ever loved, the one that made a man of me.” Albert was killed in action shortly thereafter.

Recently, I tracked down my teenage pen pal. We never met, as she lived on the other side of the country, but I got to know her well based on the many letters we exchanged. We lost touch, and when I found her again, I offered to send her the letters she’d written to me that I’d kept for all these years. When she received them, she said it was a window into her childhood, much of which she’d tucked away or forgotten after some trauma that she had suffered. I’m sorry my own children probably will never have letters to return to someone, that they’ll never know the excitement of running to the mailbox to find a five-page letter like the ones Bill used to send from 1500 miles away. There’s a tangible intimacy in letters that simply can’t be captured in a tweet or a social- media post. I think it’s time we all write a letter so that somebody’s grandma can tell them they’re loved today.